Good morning lovely readers and fellow writers.

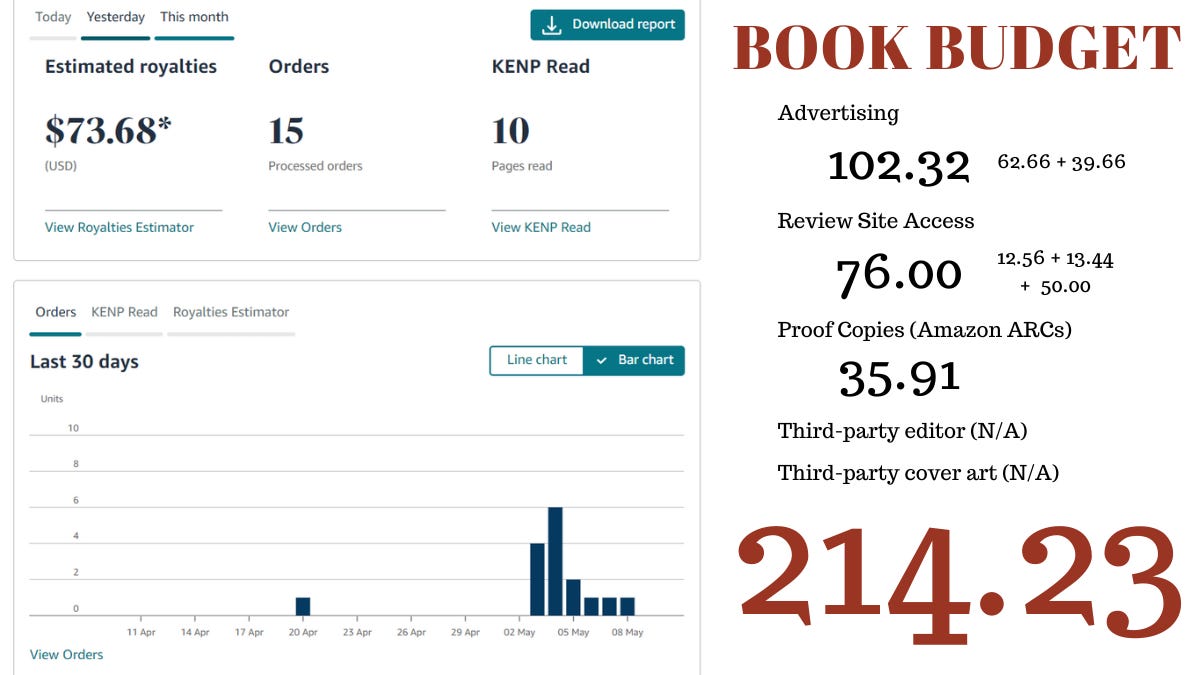

We’re just a few days out from the launch of Children of Doro, and this feels as good a time as any to talk frankly about the business of self-publishing.

May 4 was a strange day for me: quiet, yet also marking the end of an era. There was no grand launch party, no cutesy “book birthday” cakes or cupcakes; I…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Better Worlds Theory to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.