Missing Data and Worldview Gaps

Or, What Molly Conger's Weird Little Guys highlights about weak research practices

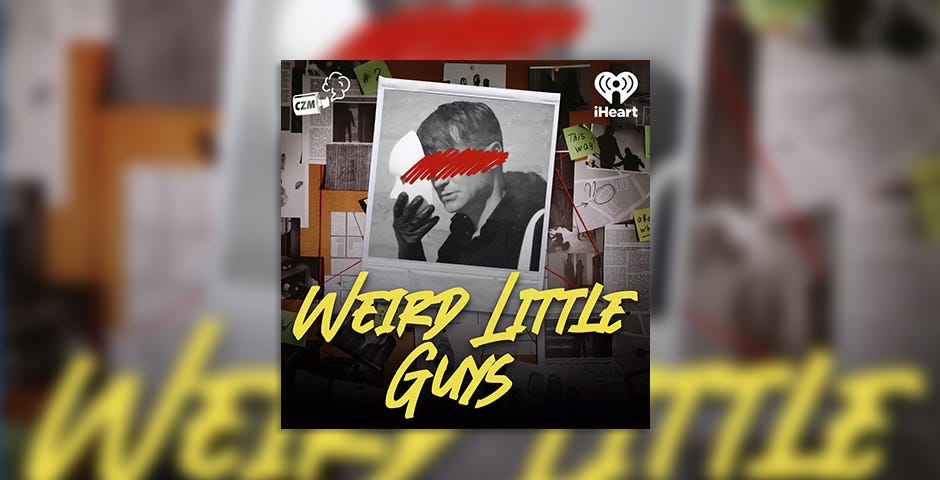

Many, many weeks ago, I started writing a piece to share a mini-series on Molly Conger’s Weird Little Guys, a podcast that mainly explores histories of people who lost themselves down white supremacist and related extremist rabbit holes, until their beliefs resulted in harm to others. In the course of Conger’s thoughtful deep-dives, she reveals larger s…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Better Worlds Theory to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.